| |

FOR

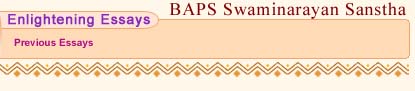

MILLENNIA HINDUS HAVE REVERED THE SANCTITY of Mt. Kailas and Manasarovar

as a heaven on earth. They are a part of the Himalayas and are situated

in northwest Tibet (or Gangdesh). FOR

MILLENNIA HINDUS HAVE REVERED THE SANCTITY of Mt. Kailas and Manasarovar

as a heaven on earth. They are a part of the Himalayas and are situated

in northwest Tibet (or Gangdesh).

The most beautiful and captivating of all the lakes in the world is

Manasarovar. Formerly, in ancient India, it was known as Brahmasar.

It is a fresh water lake perched at 15,000 ft. above sea level. Since

Vedic times thousands of years ago, it has been revered as a holy

pilgrim place and is believed to be the source of four subterranean

rivers, namely, Shatdru (Sutlej), Sindhu, Brahmaputra and Saryu (Karnali).

The Hindu scriptures called the Purans describe the death of Bhasmasur,

a demon, at this place. Many nearby landmarks are also related to

infamous and famous people of Indian culture. Ravan, the King of Lanka,

performed austerities at Ravanhrud or Rakshas Tal. The noble King

Mandhata renounced his regal comforts to perform severe austerities

at Mt. Mandhata.

The glory of Kailas1 and Manasarovar, where nature unleashes its fury

and dons its beauty, are sung at length by the shastras of Sanatan

Dharma. The Shrimad Bhagvad Gita describes Mt. Kailas as a divine

form of God, "Meruhu shikharinãmaham," meaning, "I

am Kailas (Meru) among all mountains."2

Once Rishi Dattatrey travelled from Vindhyachal Mountains in the south

to the Himalayas and then arrived at Manasarovar. After a holy dip

in its waters and seeing the royal swans (rajhansas) he asked Shiv

and Parvati residing in a cave in Mt. Kailas, "Which is the holiest

of holy places in the world?" Shivji replied, "The holiest

of holy places is the Himalaya in which lies Kailas and Manasarovar."

The Valmiki Ramayan, in the Kishkindha Kand and Bal Kand,3 and the

Bhishma Parva, Van Parva, Dron Parva and Anushashan Parva of the epic

Mahabharat describe, through stories, the glory and beauty of Kailas-Manasarovar.

According to the Uttar Puran, the first Tirthankar in Jain dharma,

Rishabhdev, performed austerities and gave up his mortal existence

at Mt. Kailas. The grandmaster of all Indian poets, Kalidas, pours

his heart in penning the grandeur of Kailas and Manasarovar in his

work called Meghdut.4

European explorers, trekkers and nature lovers have also been fascinated

by their visits. In 1906 the renowned Swedish explorer Dr. Sven Hedin

writes, "There is no finer ring on earth than which bears the

names of Manasarovar, Kailas and Gurla Mandhata; it is a turquoise

set between two diamonds. The grand impressive silence which reigns

around the inaccessible mountains, and the inexhaustible wealth of

crystal-clear water which makes the lake the mother of the holy rivers...

Whoever is of a pure and enlightened mind and bathes in the waves

of Manasarovar attains thereby to a knowledge of the truth concealed

from other mortals."5

Dr. Sven Hedin describes his first sight of Manasarovar, "Even

the first view from the hills on the shore caused us to burst into

tears of joy at the wonderful, magnificent landscape and its surpassing

beauty. The oval lake, somewhat narrower in the south than the north,

and with a diameter of about 15.5 miles, lies like an enormous turquoise

embedded between two of the finest and most famous mountain giants

of the world, the Kailas in the north and Gurla Mandhata in the south,

and between huge ranges, above which the two mountains uplift their

crowns of bright white eternal snow. Yes, already I felt the strong

fascination which held me fettered to the banks of Manasarovar, and

I knew I would not willingly leave the lake before I had listened,

until I was weary, to the song of its waves."6

Research scholars of the 'Survey of India' and intrepid explorers,

S.G. Burrard and H.H. Hayden write about Manasarovar in their book,

"Manasarovar was the first lake known to geography. Lake Manasarovar

is famous in Hindu mythology; it had in fact become famous many centuries

before the lake of Geneva had aroused any feeling of admiration in

civilised man. Before the dawn of history Manasarovar had become the

sacred lake and such it has remained for four millennium."7

In the history of humanity Manasarovar is an ancient lake. Geographically

it has been lauded as the world's first lake.

Since many eras the land of Manasarovar and Kailas has been a ground

for spiritual endeavours. Thousands of yogis, sadhus, sannyasis and

aspirants have retreated to this icy, desolate region for austerities

and meditation to realise God. Even today a visitor can experience

the vibrations of divinity of their austerities and spiritual sadhanas.

Swami Pranavanandaji, who had pilgrimaged to and stayed at Manasarovar

thirty-two times writes, "From the spiritual point of view, she

has a most enrapturing vibration of the supreme order that can soothe

and lull even the most wandering mind into sublime serenity and can

transport it into involuntary ecstasies."8

Edwin T. Atkinson, a renowned researcher who wrote the Himalayan Gazetteer,

writes about Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri, Yamunotri and the land

of Manasarovar in 1882. In his book Religion in the Himalayas Atkinson

writes about Manasarovar, "Nature in her wildest and most rugged

forms bears witness to the correctness of the belief that there is

the home of 'the great god'... All the aids to worship in the shape

of striking scenery, temples, mystic and gorgeous ceremonial and skilled

celebrants are present, and he must indeed be dull who returns from

his pilgrimage unsatisfied."9

Through the corridors of time, among the thousands of ascetics, aspirants

and explorers that trekked the most challenging land of Kailas and

Manasarovar was a peerless pilgrim called Nilkanth Varni.

More than two centuries ago, between 1792 and 1793, an eleven-year-old

child yogi called Nilkanth (later known as Bhagwan Swaminarayan) pilgrimaged

to Manasarovar alone. Details of his fascinating journey, in which

he faced untold challenges and furies of nature may seem difficult

for ordinary people to believe. But to arrive at some description

of Nilkanth's trials and tribulations we can draw parallels from the

written accounts and studies of pilgrims and explorers who had bravely

trudged and trod on the trails and lands that Nilkanth had walked.

This research will give an inkling into Nilkanth's divine persona.

The first notable account on Manasarovar was in 1715 by a European

traveller called Father Desideri.10 In 1792, when Nilkanth had embarked

upon his pilgrimage to Manasarovar, a sadhu by the name of Purana

Poori11 of Kashi described his experiences of his pilgrimage to Manasarovar

to an English official called Jonathan Duncan. The latter's write

up, 'An Account of Two Fakeers', was published in Asiatic Researches.12

The experiences of Purana Poori are fascinating. But the season in

which Purana Poori and Father Desideri journeyed to Manasarovar from

Kathmandu was less challenging and harsh than that of Nilkanth's.

About that time, in August 1792, a sannyasi named Purna Swantantra

Brahmachari Prakashanand also narrated his experiences of his pilgrimage

to Manasarovar.13 In 1796 a sadhu named Swami Harivallabh had accomplished

a pilgrimage to Manasarovar and later he had been the guide of the

English adventurers Dr. William Moorcroft (a veterinary surgeon) and

Captain Hearsay on their journey to Manasarovar via the Niti Pass

in 1812.14

In 1773 a renowned pundit, Purangir, employed as a translator by Lord

Warren Hastings, the Governor of Calcutta, pilgrimaged to Kailas-Manasarovar.

In 1808 Captain Wilford wrote a report of Purangir's visit to Kailas-Manasarovar

in 'Essay on the Sacred Isles in the West'.15 Thereafter, at the beginning

of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries many intrepid Indian and European

explorers and pilgrims visited Manasarovar and published their accounts.

We will try to understand Nilkanth's epic journey through documented

descriptions and factsheets of many explorers and pilgrims.

It would be pertinent to point out that Nilkanth's journey cannot

be compared with the treks and efforts of other explorers and pilgrims

who were partially or fully geared up for the harsh climate and terrain.

The accounts of such journeys in the last 200 years are available

in the archives in India. The accounts vividly portray how pilgrims

and adventurers fared through the frigid temperatures, with clothes,

food, guides, maps, medicines, tents, beasts of burden and porters.

In

the case of Nilkanth, what did he possess? He had a mala, kamandal,

a loincloth, a cloth wrapped around his waist, a bun of hair on his

head, no footwear and no arrangements and materials for cooking food

and setting up shelter. Nilkanth travelled alone with no maps or guides.

In the chronicles of history where thousands had travelled in one

of nature's harshest and pitiless terrains, Nilkanth's journey was

unique and matchless. The reason simply being that he journeyed at

the age of eleven, without any means or materials and wearing only

a loincloth. Also, in comparison, the other pilgrims took the easier

paths and in the favourable season. Dr. Sven Hedin and nearly all

other European trekkers took the path conducive to ponies, yaks or

Tibetan sheep which carried their supplies. In

the case of Nilkanth, what did he possess? He had a mala, kamandal,

a loincloth, a cloth wrapped around his waist, a bun of hair on his

head, no footwear and no arrangements and materials for cooking food

and setting up shelter. Nilkanth travelled alone with no maps or guides.

In the chronicles of history where thousands had travelled in one

of nature's harshest and pitiless terrains, Nilkanth's journey was

unique and matchless. The reason simply being that he journeyed at

the age of eleven, without any means or materials and wearing only

a loincloth. Also, in comparison, the other pilgrims took the easier

paths and in the favourable season. Dr. Sven Hedin and nearly all

other European trekkers took the path conducive to ponies, yaks or

Tibetan sheep which carried their supplies.

So, Nilkanth's journey to Kailas-Manasarovar was historic and unparalleled.

Even today the journey for any pilgrim, with all the necessary facilities,

rations and appropriate season, is difficult and challenging. It is

amazing how Nilkanth, a child yogi, must have accomplished his journey

in the most formidable and forbidding terrains of the Himalayas in

winter.

Nilkanth's

Journey To Manasarovar

Reports and publications subscribe the months between July and September

as ideal for a pilgrimage to Kailas-Manasarovar. Nilkanth embarked

on his journey to Manasarovar from Joshimath on 17 October 1792.16

Prior to this, from Kedarnath (11,758 ft.), he had reached Badrinath

(10,272 ft.) on 24 September 1792. He stayed here for 20 days and

on Kartak sud 1 (15 October) Nilkanth wished to travel to Manasarovar

directly from Badrinath. But the priest of Badrinath Mandir, Raval,

insisted that he come down with him to Joshimath, which he did.17

The residents of Badrinath retreat on Kartak sud 1 for six months

to Joshimath, 5,000 ft. below, to avoid the deathly cold winter and

heavy snow falls. The Badrinath Mandir is closed for six months. Nilkanth

acceded to the wishes of the priest, stayed for a few days in Joshimath

and departed for Manasarovar, up further north in the frigid winter

season.

There are twelve roads18 from India to Manasarovar. There is no reference

as to which trail Nilkanth took in the scriptures of the Swaminarayan

Sampraday. The Sampraday's scripture, Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar,

mentions that Nilkanth, after leaving from Joshimath for Manasarovar,

went to the ashram of Nar-Narayan Rishi in Badrivan. And from here

he proceeded to Manasarovar.19

Badrivan

With reference to stories from the Purans, Badrivan is a land where

Nar-Narayan Rishi performs austerities. Since it is a divine region,

beyond human perception, it is impossible for a mortal to visit it.

Despite this, according to descriptions in the Purans, Badrivan has

been geographically identified and marked by researchers. Badrivan

is a region in the Himalayas. The references given are interesting

and worthy of note.

According to the publication, The Himalayan Heritage, Badrivan or

Badrikashram20 is the region from Kanva Ashram (that is above Nandprayag)

to Mt. Satopanth (which lies 27 km northwest of Badrinath).

In a special issue of the monthly Kalyan magazine one finds details

about the location of Nar-Narayan Rishi's ashram. It says that on

the mountain behind Badrinath Mandir lies the Urvashi Kund (tank of

water). It is difficult and treacherous to reach this place. Further

ahead lies Kurma Tirth, and beyond it lies the land of Nar-Narayan's

ashram. The magazine further adds that this path is unreachable for

ordinary mortals.21 Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar also describes that

no ordinary human can reach the ashram of Nar-Narayan.22

At this juncture it is worthy to take

note of another point regarding Badrivan. On studying the mountain

range (see map next page) between Badrinath and Kedarnath, we find

Mt. Satopanth, which lies northwest of Badrinath Mandir. The mountains

Nar and Narayan lie near Mt. Satopanth. And behind these two mountains,

to its west lies Mt. Kedarnath, rising to 22,700 ft. To reach the

ashram of Nar-Narayan (or Badrikashram), the less well known and dangerous

path passes near Mt. Kedarnath. The river Arva passes by this mountain

towards Badrinath.23

Bearing this geographical account in mind let us see Nilkanth's pilgrimage

as described in Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar.24 When Nilkanth Varni

arrived at Badrivan or Badrikashram, Nar-Narayan Rishi spoke to him,

"No human can reach this place. Only if Kedarnath (the human

form of Mt. Kedar) brings someone can a person reach here."25

From this we can infer that there is some geographical relation or

connection between Mt. Kedarnath and Nar-Narayan Rishi's ashram.

In another reference the region called 'Bharat-khand' lies 10 miles

west of Mt. Satopanth in the Himalayas.26 With relation to scriptures

of the Swaminarayan Sampraday and the Purans, Nar-Narayan Rishi is

known as the king of 'Bharatkhand'.27 Swami Siddhanandmuni (also known

as Adharanand Swami), a paramhansa of Bhagwan Swaminarayan, describes

the ashram of Nar-Narayan Rishi in the chapter on Nilkanth's arrival,

"There is no other ashram like this in the region of 'Bharatkhand'28."29

From all the geographical references it is clear that Nilkanth's visit

to Nar-Narayan Rishi's ashram in Badrivan is the region that lies

between the mountains of Nar-Narayan, which is near Mt. Satopanth

that lies 23 km northwest of Badrinath. So it is in this divine, spiritual

plane, unseen to mortals, that Nar-Narayan Rishi is engaged in austerities.

On leaving Joshimath, Nilkanth reached Nar-Narayan Rishi's ashram

at Badrivan on 7 November 1792 (Kartak vad 8).30 The scripture, Shri

Haricharitramrut Sagar, states that Nilkanth performed austerities

for three months31 in the ashram of Nar-Narayan Rishi. Then in the

first week of February Nilkanth departed towards Manasarovar. Now

the question is which path did Nilkanth take?

Badrivan

To Manasarovar To Manasarovar

From Badrivan (near Mt. Satopanth), Nilkanth had only one path to

take on his journey to Manasarovar. This path passed through Mana

Ghat (Pass). Amongst all the paths to Manasarovar from India, the

one through Mana Ghat (Pass) is the least used. The reason being that

it is the most dangerous and difficult of them all.32 Nilkanth took

this challenging mountainous path, trekking 383 km, via Mana Ghat

to go to Kailas and Manasarovar.

North of Badrinath, the village of Mana (also Manibhadrapuri) is the

native of the Bhotiya tribe and is the last human settlement33 on

the path to Manasarovar. To the north of Mana village lies the Mana

Ghat at an elevation of 18,400 ft.

James Baillie Fraser, a British writer and explorer, who visited Manasarovar

in the time of Bhagwan Swaminarayan describes in his book, The Himala

Mountains, published in Britain in 1820, about the snowy and desolate

passes and regions to Manasarovar. He writes about the passes, "These

are all so dangerous and toilsome that few but the wildest inhabitants

of the most inhospitable regions choose to invade their deserts of

eternal rock and snow, where no living thing is seen, and no means

are to be obtained for preserving life."34

The region of Mana Ghat and its neighbouring lands are extremely turbulent

and frigid. Sometimes there are violent torrential showers and sometimes

severe snowfalls. One can only travel through here during the months

of May to September. A British officer Mr. Trail writes, "An

interval of four months without a fall of snow is rare. Snow begins

to fall about the end of September and continues to accumulate to

the beginning of April. It is intensely cold during this period...

In open and level situations, unaffected by drifts or avalanches,

the bed of snow reaches at its maximum depth from 6 to 12 feet..."35

When Nilkanth was travelling through Mana Ghat it was February. To

understand the climatic conditions, a well known Indian writer, Rai

Pati Ram Bahadur, in his book Garhwal, Ancient and Modern, published

in 1900, states that between December and April the region is desolate,

overwhelmed with snow and human-less.36

The Mana Ghat is covered with snow all the year round. In July 1929

Swami Tapovanji and Swami Krishnashramji travelled to Manasarovar

through the region of Mana Ghat. From their descriptions one can infer

the rigours and hardships of Nilkanth's journey. Let us once again

remind ourselves that Nilkanth was only 11 years old, travelling alone,

wearing only a loincloth and with no food or material provisions whatsoever.

He crossed the Mana Ghat in the bitter, winter month of February.

Swami Tapovanji, in his book, Wanderings in Himalayas writes his experiences,

"On the sixth night we pitched our tents five to six miles below

Mana Ghat. Thereafter we made a steep ascent. There were huge rocks

and glaciers. There was not an inch of land we could see. At 18,400

ft. the deficiency of oxygen in the air made our heads ache and split

terribly. This was not the case for us pilgrims alone, but the Bhotiya

people who travelled this region frequently also experienced the same.

The three to four wild horses, belonging to some businessmen accompanying

with us, were carried away by a small river. One of them died due

to exhaustion and weakness. The businessmen said that this happens

every year. Death comes seeking no permission and neither does it

allow anyone to say their goodbyes.

"The head or tip of Mana Ghat is a sea of ice and snow. Here

there is a frozen lake called Devsar, with a circumference of 10-12

furlongs. We started walking from early morning. Two miles later we

arrived at a holy place on Mana Ghat. Then we walked a further five

miles and descended the Ghat. Our great sages took this trail on their

pilgrimage to Kailas. We saw a tiger, locally called saku. It preys

upon wild horses."37

A contemporary issue of a British gazetteer describes that in the

winter season (in which Nilkanth travelled) the land is covered with

abundant glaciers.38 To cross such a terrain was a challenge.

In 1946 a sannyasi scholar of Uttar Kashi, Swami Prabodhanandji,39

and five more sannyasis, with a guide, crossed a glacier between Gaumukh

(the origin of river Ganga) and Badrinath. Swami Prabodh-anandji describes

their pains and difficulties (translated from Swami Anand's Gujarati

version, "Our feet, by walking in mud and slush and jumping on

rocky ground, became so numb that we all felt like lying down to sleep.

"The winter snow was frozen as it was. Our bare soles of feet

were numb, sore and inflicted by deathly pain. Outside our feet were

insensitive and inside throbbing with pain."

And what was it like to stay the night in such conditions? Swami Prabodhanandji

writes, "It was impossible to get a wink of sleep in the bone-chilling

and numbing glaciers that were like transparent glass. And yet we

had no other recourse but to spend a night on the frigid, deathly

surface of the glacier. Before the night would end there was a possibility

that we would all freeze like a horn and by morning none of us would

be able to open our eyes at all."

The glacier surface is hard but inside one may find slush and mud

that act like quicksand, swallowing a person once he falls in it.

The fog makes walking difficult. Prabodhanand Swami and his team,

though connected with ropes, experienced a fall in a mud-slush hole.

He writes, "As we were advancing, Dalipsingh, our guide, suddenly

collapsed into a waist-deep pool of mud and slush. We quickly pulled

him out. Then when we had progressed a little further the ice broke

again and he fell into another pool. The glacier had an ankle-deep

layer of snow on it. It was impossible to tell where the ice would

break and plunge one into a pool of mud and slush. Furthermore, the

fog was so dense that one could grab a fistful and could not know

where our guide had fallen. We knew he was in grave difficulty and

anxiety. Then we heard his voice, 'Don't move one step from where

you are. We are all on the edge of a crevasse. I can see no bottom

to it!'

"We were all fixed in a dangerous position. We were like an advancing

caterpillar suddenly with its hind part anchored to the edge of a

branch and its front part exploring in mid-air!

"Then we had to cross a third sea of ice. Again we came across

mud and slush pools. Every step was full of adversities. In all we

managed through 10 to 15 mud-slush pools without losing our patience

and with great care and alertness.

"At one point Dalipsingh shouted from behind us, 'Now move to

your right. Untie your ropes. Walk freely. There is no need to walk

connected to each other.' We did as we were told. Dalipsingh then

went up front rolling the rope together. We again came across a path

laden with stones and rocks. As evening came the thick fog suddenly

changed into a black cloud. We could not see the person in front.

Large chunks of snow came raining down. There was a blitzkrieg of

snow, glacier, mud-slush pools and thunderbolts."40

From the above narration one cannot but be left wondering as to how

Nilkanth had crossed Mana Ghat in even more terrible conditions during

February. Another deathly obstacle that Nilkanth must have faced were

avalanches. Avalanches and landslides are common in this terrain.

Travellers are in constant danger of landslides.

Edwin T. Atkinson in the Himalayan Gazetteer writes about the dangers

of Mana Ghat, "The necessity of travelling for many miles over

the vast accumulations of loose rock and debris brought down by ancient

glaciers, or which violent atmospheric changes have thrown down into

the valley from the mountains on both sides, render the Mana Pass

one of the most difficult in this part of the Himalaya."41

Swami Prabodhanand and guide Dalipsingh explain their experiences

of avalanches and landslides,42 "Now we have entered the region

where the snow and glaciers have not melted since ages. The sides

of the glacier we were walking on were touching high walls of ice

and snow. Suddenly we heard loud rumbling sounds from the mountain

peaks. Was it the sound of rain or was it the clouds! There was no

need for an answer. Up high from the mountain slopes we saw huge boulders

of snow hurtling down. The boulders of snow filled the slopes of the

mountain on its way down. The snow attacked aggressively, filling

the curb of the path which we had passed a few minutes before. This

we saw with our naked eyes! It was an avalanche. It occurs every day.

"But before we could regain our senses from that phenomena, in

a single eye blink, dark black clouds suddenly descended upon us from

over the peaks. The onslaught of rain and hail temporary blinded us

all. Our next camp site was only two 'farms' away. We made courageous

efforts to reach it, but simply couldn't do it!

"Our silent, naked sadhu and the rest of our friends shivered

as if stricken by a terrible, cold fever. Our eyes and noses leaked

copiously. Our beards and moustaches turned white because of snow.

The air from our mouths turned into white smoke and then immediately

into ice particles. Without any other option, we set up our tent by

the rock wall on the glacier, wrapping our shivering friends to sleep!

"We were terribly thirsty. But from where could we get water.

Everywhere around us there was only snow and ice. There was fresh

snow falling constantly. I went out to look for a small water hole.

And, I soon found one. I filled the glass and started drinking. But

I couldn't drink even a mouthful. So I drank a little, drop by drop.

I filled it again and came to the tent.

"The cold was biting us like an attacking dog. I was worried

about my friends exposed to the cold. An ice cap formed over my open

head."43

It is chilling to imagine as to how Nilkanth must have travelled from

Mt. Satopanth and crossed Mana Ghat through the severe winter cold,

avalanches and landslides. It can be crossed only between July and

September. Among all its challenging hardships is its height. The

Mana Ghat lies at 18,400 ft. above sea level. While passing through

at that height Swami Prabodhanand writes, "We felt tired even

when we talked briefly and softly. The air at 18,000 ft. and above

is so thin that even in the supine position we gasped for air while

breathing. While climbing we breathed like bellows. After every third

step we stopped and inhaled nine times. Our body, soul and vital airs

were simply exhausted. Each step we made was accomplished with great

labour and pain.

"Our mind has really been numbed. How can we travel without a

compass in this vast, endless ocean of snow! Where should we turn!

So we endeavoured with our last resources. The terrible fiery reflection

of the afternoon sun on the snow blinded our eyes and left them in

a painful state! On travelling without wearing reflective goggles

for three days, our eyes pained dangerously and drained with water.

We couldn't even open them enough to see the road. And as if this

was less, the intense fog returned again and enveloped us. We couldn't

even see each other!

"Our mind has really been numbed. How can we travel without a

compass in this vast, endless ocean of snow! Where should we turn!

So we endeavoured with our last resources. The terrible fiery reflection

of the afternoon sun on the snow blinded our eyes and left them in

a painful state! On travelling without wearing reflective goggles

for three days, our eyes pained dangerously and drained with water.

We couldn't even open them enough to see the road. And as if this

was less, the intense fog returned again and enveloped us. We couldn't

even see each other!

"When we descended we felt our eyes had films of fog layered

on it. Hence, whatever we saw it appeared double or treble. We could

not even recognise whether there is a human or an animal a short distance

away! The snow's bright reflection distorts or damages vision. And

the distortion endures for upto two to three weeks. Permanent damage

is however very rare."44 (Translated from Gujarati script.)

Nilkanth must have faced the extremes of the winter climate while

crossing the Mana Ghat. Thereafter he walked at an altitude of 12,500

ft. for 20 miles, then climbed to 16,400 ft. to cross Charang Ghat.45

Nilkanth

Enters The Tibetian plains Enters The

Tibetan Plains

After crossing Mana Ghat, Nilkanth walked for four days to reach a

Buddhist hermitage called Thhuling Math (12,200 ft.), which is 160

km of mountainous terrain from Badrinath. From here Nilkanth entered

the Tibetan Plains which are at a height of 12-14,000 ft. By inference

Nilkanth must have visited and stayed at the Thhuling Math.46 We don't

have any information whether the inmates were staying in February

or during the winter months. The reason why Nilkanth may have visited

the Thhuling Math is that it was formerly the seat of Lord Badri.

And Nilkanth would have never missed visiting such a historic pilgrim

place.

Swami Tapovanji writes about the Thhuling Math, "The main residing

murti is of Bhagwan Buddha... The lamas of this monastery say the

murti of Buddha is in fact that of Badrinarayan. This is the original

place, but because of its inaccessibility and harsh terrains it was

changed to the present place of Badrinath that is over the mountain

on a lower altitude."47

A problem that pilgrims faced while

travelling to Thhuling Math was of some wild, unruly local people.

They lived in mountain caves or in huts set up in the mountain valley.

They were giant in size, robbing and even killing travellers and pilgrims.

In 1838 these wild locals killed the famous British researcher and

traveller Dr. William Moorcroft near Manasarovar.48 Swami Tapovanji

writes about these wild, meat-eating people, "Sheep and cows

are slaughtered unchecked in Tibet. So it is natural that the heaps

of bones, hooves and horns that one finds along the way are appalling.

These people eat raw meat."49 (That is why our Purans have mentioned

them as pishachos - evil people.)

From Thhuling Math to Manasarovar the trail is full of ice cold winds.

The boisterous rivers and channels that cross the trail are without

bridges. This makes it difficult for pilgrims to cross. The only alternative

left is by wading through chest-deep cold water and risking one's

life.

A century ago, in 1900, Ramsharan Vidyarthi, a well-known advocate

and Hindi writer of Delhi writes about his journey in this terrain,

"You do not find any animals nor any lush trees here. Everywhere

an extremely deathly cold wind hovers over you. And every second the

fear of dacoits prevails in your heart. So the cold and the dacoits,

who are like death, are the sources of constant fear. The currents

of water and air are too strong. They flow unchecked and unbridled.

In this lifeless, dead, terrifying, unknown 'jungle' we advanced on

ponies at a very slow pace. From morning till evening we walked on

in absolute silence, lost in self-introspection and half conscious

in this stunningly noiseless 'forest'. In this land created by God

one cannot see the trace of any human form. Everywhere there is one

colour, a desolate path that rolls ahead unchanging and certain. In

this semi-conscious state before my mental eye I saw in the countless

rocks a lustre similar to the stars in the sky. God's light remains

aflame."50

The terrain ahead of Thhuling Math is predominantly full of rocky

plains. At 12,000 to 14,000 ft. this desolate terrain is subject to

sudden turbulent weather changes that leaves any traveller subdued.

Ramsharan Vidyarthi describes further, "When we were preparing

to rest for the night the prevailing peace started taking on a deathly

form. In reality this peace was an indication of a destructive storm

or blizzard. We all entered and sat in our own tents, shocked and

amazed. Whilst looking we saw a blue sky transform into a white sky.

Quietly and peacefully it started snowing. The ground became covered

by a carpet of snow. Our sight was filled with the donning of a full-fledged

coat of thick white (snow). All the trees and plants were covered

in snow. Even sheep, goats and cows were covered with the white fabric

of snow."51

The snowfall then turns turbulent into a deathly blizzard. In 1906

and 1908 the Swedish traveller, Sven Hedin, faced many such difficulties

in the course of his journey to Manasarovar. His description in his

book, Trans Himalaya,52 of destructive blizzards is hair-raising (see

above picture). Sven Hedin lost twelve horses and men. Sometimes when

the yaks, used for transport, turn violent and attack humans, lives

are lost. Sven Hedin lost his guide because of a yak attack. Despite

being fully equipped with materials and men, Sven Hedin just about

managed to complete his travellings. It is amazing how Nilkanth, a

young, tender boy of only eleven years managed to negotiate, bear

and overcome the challenges he met on his way to Manasarovar.

The snowfall then turns turbulent into a deathly blizzard. In 1906

and 1908 the Swedish traveller, Sven Hedin, faced many such difficulties

in the course of his journey to Manasarovar. His description in his

book, Trans Himalaya,52 of destructive blizzards is hair-raising (see

above picture). Sven Hedin lost twelve horses and men. Sometimes when

the yaks, used for transport, turn violent and attack humans, lives

are lost. Sven Hedin lost his guide because of a yak attack. Despite

being fully equipped with materials and men, Sven Hedin just about

managed to complete his travellings. It is amazing how Nilkanth, a

young, tender boy of only eleven years managed to negotiate, bear

and overcome the challenges he met on his way to Manasarovar.

The path from Thhuling Math to Manasarovar is approximately at an

altitude of 14,000 ft. In the mild seasons one finds small markets

(mandis) of five to twenty-five tents dotted along the way. During

the winter season the markets disappear, with its owners doing business

on more favourable grounds.

On advancing from Thhuling Math to Manasarovar Nilkanth must have

passed through various places and rivers like Mangang (11 miles),

Dapa (14 miles), Nabra Mandi (market) (6.5 miles), River Gomal Chhu

(5.75 miles), River Dongpu (7.5 miles), River Dongu (19.5 miles),

River Tisum (3.75 miles), Shibchilam Mandi (19 miles), Manithanga

(7.25 miles), Gombachen (3.5 miles), River Guni Yankti (15 miles),

River Dharma Yankti (3.75 miles), Gyanima Mandi (13 miles), Chhumikshala

(16.5 miles) and others.53 Having crossed the forbidding terrain Nilkanth

must have also crossed the river Sutlej and arrived in Tarchhen, which

lies at the foot of Mt. Kailas. With his journey in February, Nilkanth

must have confronted heavy snowfalls and biting cold winds. One has

to cross Tarchhen (15,100 ft.)54 while travelling from Thhuling Math

towards Manasarovar. Tarchhen lies at the foot of Mt. Kailas (22,022

ft.) and northwest of Manasarovar. First one has the darshan of the

beautiful, holy Mt. Kailas. The divine experience of Mt. Kailas transforms

even the diehard atheist. The present day modern settlement in Tarchhen

was not existent 200 years ago when Nilkanth visited it. According

to the British traveller, Dr. William Moorcroft, who visited it in

1812, there were only four houses of unburnt brick or stones and about

twenty-eight tents."55

Nilkanth's

parikrama of Mt. Kailas Parikrama of

Mt. Kailas

Pilgrims begin their parikrama (circumambulation) of Mt. Kailas from

Tarchhen. With Nilkanth's travel route from Thhuling Math it seems

that he may have embarked upon the parikrama of Mt. Kailas without

first coming to Tarchhen. Though there is no information of Nilkanth's

parikrama of Mt. Kailas in the scriptures or records of the Swaminarayan

Sampraday, it seems that he must have performed it. The reason being

that it would be easier for him to reach Manasarovar after completing

the parikrama. Another reason being that people, then, considered

it highly meritorious to do the parikrama, as people do today. Normally

it takes three days to complete the parikrama.

Swami

Tapovanji, who took the same route as Nilkanth, from Thhuling Math

to Manasarovar, shares his experience of his parikrama of Mt. Kailas.

He says, "In the sun's light the snow-capped peak of Mt. Kailas,

which is 22,022 ft. high with a circumference of 28 to 30 miles, looked

illustrious as silver. Its beauty was matchless and divine. To perform

the parikrama of Kailas on rough grounds, replete with rocks, water

and snow, and in the severe cold of 18,000 to 19,000 ft. altitude

is truly a test of one's austerity and faith. Swami

Tapovanji, who took the same route as Nilkanth, from Thhuling Math

to Manasarovar, shares his experience of his parikrama of Mt. Kailas.

He says, "In the sun's light the snow-capped peak of Mt. Kailas,

which is 22,022 ft. high with a circumference of 28 to 30 miles, looked

illustrious as silver. Its beauty was matchless and divine. To perform

the parikrama of Kailas on rough grounds, replete with rocks, water

and snow, and in the severe cold of 18,000 to 19,000 ft. altitude

is truly a test of one's austerity and faith.

"On advancing six to seven miles from Tarchhen we reached Chakku

Lamaserai (a Buddhist monastery). After a little rest we travelled

about five miles to Dirfuk and rested for the night. It rained and

snowed heavily at night. The view of Mt. Kailas from here is so clear

that one does not find it anywhere else. So we did darshan of Kailas

in the evening and morning. We left in the morning. In the beginning

we had a very steep climb. The Dolma Ghat is at 18,600 ft. There is

a beautiful lake called Gauri Kund. It is believed that Parvati swims

here. We trudged through the deep snow and reached the banks of the

lake. The lake had scattered heaps of ice and on its surface was a

two to three inch layer of transparent ice... While doing the parikrama

we had to walk on the banks of fast flowing streams and in valleys

of the world's highest mountains. And so our trek was a pious austerity.

It is difficult to describe it all."56

The land of Kailas-Manasarovar is freezing cold and battered by howling

winds. From November to May, along with heavy snowfalls and blizzards,

there are tempestuous winds. The land is also subject to the vagaries

of climate; where thick, black clouds suddenly and angrily pelt the

terrain with ice and snow. Narrating his experiences of Kailas parikrama,

Ramsharan Vidyarthi writes, "In certain places our feet easily

sank into one to one-and-a-half feet of snow. The spread of snow is

so much that one has to walk continuously on it for two to three furlongs.

Then before one's eyes one can see a carpet of snow. The sight is

very beautiful. On this place (Kailas) lies the origin of the river

Sindhu. From the snow is born the river Sindhu. While walking on the

countless icy boulders to reach Kailas we place every step with great

care. After some time this exercise to advance further in this manner

made us feel that we may lose our lives. We knew clearly that to walk

ahead would be like drowning in ice.

"In these conditions we climbed four miles and reached Gauri

Kund. On the way we had to walk on snow in many places and experienced

difficulties in breathing. The headaches made our hearts anxious.

The climbing ends at 18,600 ft...

"On the (mountain) top, to the right is a mirror-like, shining

lake covered with ice that is approximately one furlong wide and three

furlongs long. Beneath the two to three feet large lid of ice is a

pool of water. One can see a patch of ice-free water on one side only.

To take a dip in this lake is a matter of great courage or foolishness.

To dip one's hand in its waters and then take it out is very difficult.

Then who would dare to take a dip and come out dead! To come out of

these waters is in reality to bring out a dead body. An old pundit

in our team became numb. On coming out, contrary to the warnings from

the guides, he loudly hailed the name of Umapati (Shivji) and became

unconscious. Due to the cold his body seemed to be lifeless."57

When the pilgrims succeed in overcoming all the severe trials and

difficulties the panoramic beauty of Manasarovar redeems them from

all pain and suffering. Every pore is overwhelmed with joy. Manasarovar

is 20 km southeast of Mt. Kailas. Swami Tapovanji writes, "After

proceeding from Kailas towards Manasarovar, we had to cross many streams...

Manasarovar is at a height of 15,000 ft. All around there are no plants,

and it is surrounded by snow-capped black mountains. When the winds

are turbulent the lake bristles with huge waves. And when the winds

die then its deep, blue waters are calm. I do not believe that the

beauty of this beautiful lake lies anywhere else on earth. At the

time of dusk its beauty is so unique that philosophers experience

samadhi."58

Nilkanth Varni's experience after circumambulating Mt. Kailas and

arriving at Manasarovar was immensely different from that of Swami

Tapovanji. The reason being that the winter time in which Nilkanth

was there, the entire 518 sq. km Manasarovar was frozen.

O, what beauty Manasarovar must have donned, and at the same time

how harsh and callous it must have been! In the succeeding pages let

us look at Nilkanth's brief stay at Manasarovar.

Footnote

-

Kelinãm samuhah

kailam tena ãsyate sthiyate iti Kailasah (Ãs Upveshane)Ð

meaning, "Where Shiv (happiness) and Prakriti (nature and daughter

of Himalaya) are always engrossed in a dance is Kailas."

-

Bhagvad Gita:10/23.

-

Sugriv says to all

the monkeys, "After crossing the dangerous forest, you will

be very happy to see the snow laden Kailas mountain."

Tattu shrigramatikramya kãntãram romharshanam-kailsãm

pãnduram prãpya hrashtã yuyam bhavushyathÐ

(Kishkindha Kand: 43-20).

Further, in 43-21, Manasarovar is described in detail.

Kailãsparvate Rãm mansã nirmitam paramÐ

Brahmanã narshãrdul tenedam mãnasam sarahH

(Bal Kand: 24-8).

-

Part 1, 60.

-

Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya,

Discoveries and Adventures in Tibet, Vol. 3. London: MacMillan and

Co. Limited, 1913: 189.

-

Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalayas,

Discoveries and Adventures in Tibet, Vol. 2. p. 111.

-

Burrard, S.G. and

Hayden, H.H. A Sketch of the Geography and Geology of the Himalaya

Mountains and Tibet, Part-3. Delhi: Survey of India, 1934: 228.

-

Swami Pranavananda.

Kailas-Manasarovar, 1st ed. Calcutta: S.P. League, Ltd., 1949: 7.

-

Atkinson, E.T. Religion

in the Himalayas. 1974: 23.

-

Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya,

Vol. 3. p. 196.

-

He was a Kshatriya

Rajput from Kanoj. He was an 'urdhvabahu' sadhu.

-

Duncan, Jonathan.

Asiatic Researches, Vol. 5. Calcutta: Asiatic Society, 1808. Reprinted,

New Delhi: Cosmo Publication, 1979: 37-52.

- ibid, Vol. 5. p. 49.

- Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya, Vol. 3.

p. 212-216.

- Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya, Vol. 3.

p. 208.

-

16. Dave, Harshadray

T. Bhagwan Swaminarayan, Vol. 5. Amdavad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith,

1987: 567.

-

17. Swami Shri Siddhanandmuni

(also known as Swami Adharanandmuni). Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar.

Varanasi: Swami Hariprakash, Pundit Shrinarmadeshwar Chaturvedi,

1972: 364.

18. Swami Pranavananda. Kailas-Manasarovar, 1st ed. Calcutta: S.P.

League, Ltd., 1949: 111-145.

19. Swami Shri Siddhanandmuni (also known as Swami Adharanandmuni).

Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar. Varanasi: Swami Hariprakash, Pundit

Shrinarmadeshwar Chaturvedi, 1972: 366-377.

20. Kaur, Jagdish. Badrinath: A Study in Site Character, Pilgrims

Patterns and Process of Modernisation. In The Himalayan Heritage.

1st ed. Delhi: Gian Publishing House, 1987: 224.

Another story about Badrivan in the Purans says that Badrivan is

in the Himalayan region, north of Badrinath on the banks of the

River Sutlej. Today it is known as Thhulingmath. Many millennia

ago a tribe of brute people indulged in meat eating. So Narayan

Rishi left that region and came to Mana Pass by the banks of river

Alaknanda and settled down to perform austerities. Seeing her lord

performing austerities in the open snowy terrain, Lakshmiji took

the form of a Badri (berry) tree and spread her branches like a

shelter above him. From thenceforth Narayan Rishi named his place

as Badrikashram. Gradually the Badri trees flourished in the ashram.

In 1882, a British writer, Edwin T. Atkinson, notes in the Himalayan

Gazetteer that formerly the place must have been full of berry (Badri)

trees but now there weren't any.

Atkinson, Edwin T. The Himalayan Gazetteer, Vol. III Part-II. New

Delhi: Cosmo Publications, 1973: 23.

21. Poddar, Hanumanprasad. Tirthank. Gorakhpur: Gita Press 1957:

60.

22. Swami Shri Siddhanandmuni (also known as Swami Adharanandmuni).

Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar. Varanasi: Swami Hariprakash, Pundit

Shrinarmadeshwar Chaturvedi, 1972: 2-18-18, p. 370.

-

23. "Both the

Satopanth and Kedar peaks were scaled from Gaumukh side and the

shortcut to Badrinath via Arva valley and Ghastoli was also negotiated."

Swami Pranavananda. Kailas-Manasarovar. p. 158.

24. Nilkanth Varni, on arriving in Loj, Gujarat, had narrated his

travellings to Muktanand Swami. From his notes Swami Siddhanand

(Adharanandmuni) wrote this scripture in Hindi verse.

25. Swami Shri Siddhanandmuni (also known as Swami Adharanandmuni).

Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar. Varanasi: Swami Hariprakash, Pundit

Shrinarmadeshwar Chaturvedi, 1972: 2-18-18, p. 370.

26. Bahadur, Rai Pati Ram. Garhwal, Ancient and Modern. Gurgaon:

Vintage Books, 1992, p. 17.

27. Dave, Harshadray T. Bhagwan Swaminarayan, Vol. 4. Amdavad: Swaminarayan

Aksharpith, 1987: 323.

28. A part of the nine khands of Bharatvarsh, Bhagvadgomandal, p.

6603.

29. Swami Shri Siddhanandmuni (also known as Swami Adharanandmuni).

Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar. Varanasi: Swami Hariprakash, Pundit

Shrinarmadeshwar Chaturvedi, 1972: 2-17-40, p. 369.

-

30. Dave, Harshadray

T. Bhagwan Swaminarayan, Vol. 5. Amdavad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith,

p. 567.

30. Swami Shri Siddhanandmuni (also known as Swami Adharanandmuni).

Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar. Varanasi: Swami Hariprakash, Pundit

Shrinarmadeshwar Chaturvedi, 1972: 2-19-15, p. 373.

-

32. Swami Pranavananda.

Kailas-Manasarovar. p. 155-157.

33. "The Bhotiya village of Mana is the last human settlement

of this region." Kaur, Jagdish. The Himalayan Heritage. p.

223.

A British Officer, Captain Raper, had visited the village of Mana

in 1802. At that time there were around 150 houses.

-

34. Fraser, James

Baillie. The Himala Mountains. Delhi: Neeraj Publishing House, Reprint

1982: 284.

35. Bahadur, Rai Pati Ram. Garhwal, Ancient and Modern. Gurgaon:

Vintage Books, p. 37.

36. Bahadur, Rai Pati Ram. Garhwal, Ancient and Modern. p. 37.

-

37. Bhuta, Maganlal

J. Uttarapath. Mumbai: Parivrajak Prakashan, 1977: 217-8 (A translation

of the Gujarati script).

38. Atkinson, E.T. Himalayan Gazetteer. Vol.3, Part 2, p. 583.

39. In 1929, Swami Prabodhanandji graduated in Philosophy from Siyalkot.

-

40. Swami Anand.

Baraf Raste Badarinath. Amdavad: Balgovind Prakashak, 1970: 58,

64, 74-78 (All quotes are a translation of the Gujarati script).

41. Atkinson, E. T. The Himalayan Gazeteer, Vol. 3, Part 2. p. 582.

42. Swami Anand, Baraf Raste Badarinath. p. 59-64.

-

43. Swami Anand.

Baraf Raste Badarinath. p. 59-64.

-

44. Swami Anand.

Baraf Raste Badarinath. p. 66, 86.

45. Swami Pranavananda. Kailas-Manasarovar. p. 155-157.

46. "Thhuling Gompa, classically known as Thunding, is situated

on the left bank of the river Sutlej at a distance of about a mile

from the edge of water. This was founded in A.D. 1030 and is the

most famous monastery in Western Tibet. Turks had pillaged this

monastery on more than one occasion and set fire to it when, several

hundreds of valuable Sanskrit and Tibetan manuscripts were reduced

to ashes. The great Acharya Deepankara Shreejnana of Nalanda University

fame came here in 1042 to preach Buddhism. He sojourned here for

nine months and wrote many books including translations."

- Swami Pranavananda. Kailas-Manasarovar. p. 156.

47. In the Van Parva of Mahabharat, Badarinath is shown to be near

Kailas.

Kailãsah parvatorãjan shadyojansamuchhitah yatra devã

samãyãnti vishãlã yatra Bhãrat.

(Mahabharat, Van Parva, 1-24, 139-11)

Since a long time there has been a relation of give and take between

the pujari of Badrinath mandir and the Lama priest of Thhuling Math.

"...Before the Mana Pass is blocked up with snow, the abbot

(of the Thhuling Math) sends every year some offerings to Badrinath

temple and in return gets some prasad from the pujari or Raval of

Badrinath..."

Swami Pranavananda. Kailas-Manasarovar. p. 157.

In this context see also footnote no. 20.

48. Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya, Vol. 3. p. 216.

49. Bhuta, Maganlal J. Uttarapath. p. 219.

50. Vidyarthi, Ramsharan. Kailas-path Par. Delhi: Sharda Mandir

Limited, 1902: 79.

51. Vidyarthi, Ramsharan. Kailas-path Par. p. 84.

-

52. Hedin, Sven.

Trans-Himalaya, Vols. 1 & 2.

53. Swami Pranavananda. Kailas-Manasarovar. p. 155-157.

54. Swami Pranavananda. Kailas-Manasarovar. p. 157.

55. Atkinson, E. T. Religion in the Himalays, Vol. 3, Part 2. p.

377.

56. Bhuta, Maganlal J. Uttarapath. p. 221.

- 57. Vidyarthi, Ramsharan. Kailas-path

Par. p.106-108.

58. Bhuta, Maganlal J. Uttarapath. 1977: 217-8

.

Gujarati

text: Sadhu Aksharvatsaldas

Translation: Sadhu Amrutvijaydas

Further related

articles will be placed on the set dates in this section

|

|